Compared to other primates, humans have remarkably large brains relative to their body sizes. The resultant high demands for glucose may have been supported by changes in the gut microbiota, which can influence host metabolism. In this study, we tested this idea by inoculating germ-free mice with gut microbes from three primate species varying in brain size. Brain gene expression differences between mice inoculated with human versus macaque gut microbes mirrored patterns observed in human versus macaque brains, and human gut microbes stimulated glucose production and use in the mouse brain. The findings suggest that species differences in gut microbiota can influence brain metabolism and raise the possibility that the gut microbiota may have supported the energetic demands associated with larger brains in primates.

DeCasien et al. provide the first empirical data showing the direct role the gut microbiome plays in shaping differences in the way the brain functions across different primate species. Image credit: DeCasien et al., doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122.

“Our study shows that microbes are acting on traits that are relevant to our understanding of evolution, and particularly the evolution of human brains,” said Northwestern University researcher Katie Amato, senior author fo the study.

The study builds upon previous findings that showed the microbes of larger-brained primates, when introduced in host mice, produced more metabolic energy in the microbiome of the host — a prerequisite for larger brains, which are energetically costly to develop and function.

This time, the researchers wanted to look at the brain itself to see if the microbes from different primates with different relative brain sizes would change how the brains of host mice functioned.

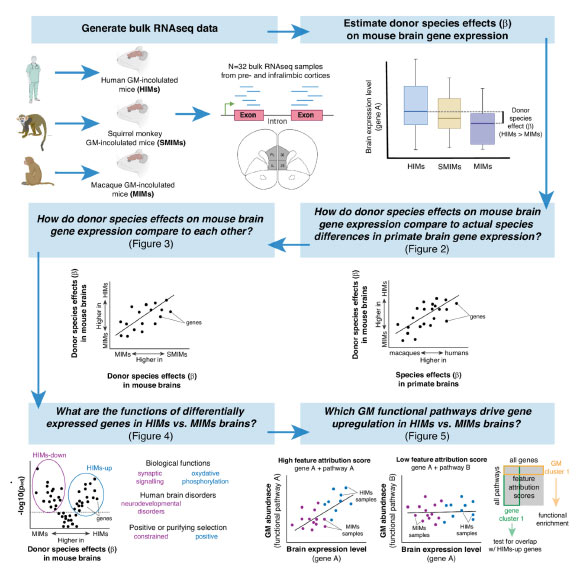

In a controlled lab experiment, they implanted gut microbes from two large-brain primate species (human and squirrel monkey) and one small-brain primate species (macaque) into microbe-free mice.

Within eight weeks of making changes to the hosts’ microbiomes, they observed that the brains of mice with microbes from small-brain primates were indeed working differently than the brains of mice with microbes from large-brain primates.

In the mice with large-brain primate microbes, the scientists found increased expression of genes associated with energy production and synaptic plasticity, the physical process of learning in the brain.

In the mice with smaller-brain primate microbes, there was less expression of these processes.

“What was super interesting is we were able to compare data we had from the brains of the host mice with data from actual macaque and human brains, and to our surprise, many of the patterns we saw in brain gene expression of the mice were the same patterns seen in the actual primates themselves,” Dr. Amato said.

“In other words, we were able to make the brains of mice look like the brains of the actual primates the microbes came from.”

Another surprising discovery the authors made was a pattern of gene expression associated with ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar and autism in the genes of the mice with the microbes from smaller-brained primates.

While there is existing evidence showing correlations between conditions like autism and the composition of the gut microbiome, there is a lack of data showing the gut microbes contribute to these conditions.

“This study provides more evidence that microbes may causally contribute to these disorders —specifically, the gut microbiome is shaping brain function during development,” Dr. Amato said.

“Based on our findings, we can speculate that if the human brain is exposed to the actions of the ‘wrong’ microbes, its development will change, and we will see symptoms of these disorders, i.e., if you don’t get exposed to the ‘right’ human microbes in early life, your brain will work differently, and this may lead to symptoms of these conditions.”

The findings appear today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

_____

Alex R. DeCasien et al. 2026. Primate gut microbiota induce evolutionarily salient changes in mouse neurodevelopment. PNAS 123 (2): e2426232122; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2426232122