Bees are well known for their species and remarkable behavioral diversity, ranging from solitary species that nest in burrows to social species that construct highly compartmentalized nests. This nesting variation is partially documented in the fossil record through trace fossils dating from the Cretaceous to the Holocene. In a new paper, Field Museum paleontologist Lazaro Viñola López and colleagues described a novel nesting behavior based on trace fossils recovered from a Late Quaternary cave deposit on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola: isolated brood cells, named Osnidum almontei, were found inside cavities of vertebrate remains.

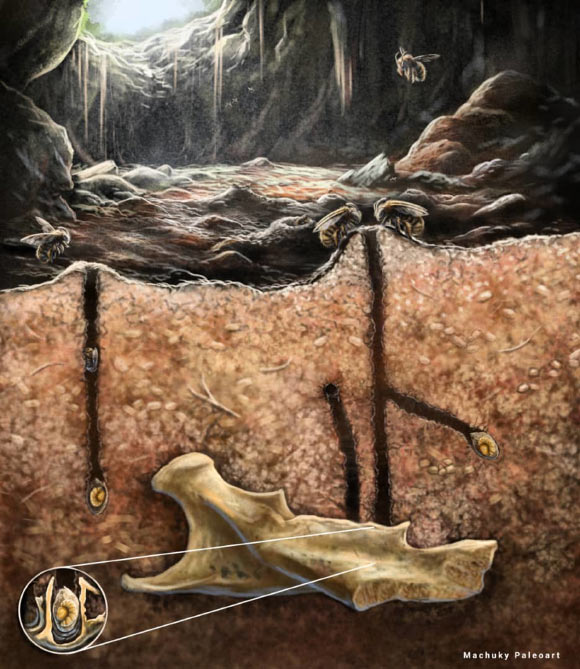

Life reconstruction of the tracemaking bee nesting inside a cave and using bone cavities as containing chambers for some of the brooding cells. Image credit: Jorge Mario Macho.

“The initial descent into the cave isn’t too deep — we would tie a rope to the side and then rappel down,” Dr. Viñola López said.

“If you go in at night, you see the eyes of the tarantulas that live inside. But once you walk down a ten-meter-long tunnel underground, you start finding the fossils.”

There were layers and layers of fossils, separated by carbonate layers resulting from rainy periods in the distant past.

Many of the fossils belonged to rodents, but there were also bones from sloths, birds, and reptiles amounting to more than 50 different species. Taken together, these fossils told a story.

“We think that this was a cave where owls lived for many generations, maybe for hundreds or thousands of years,” Dr. Viñola López said.

“The owls would go out and hunt, and then come back to the cave and throw up pellets.”

“We find fossils of the animals that they ate, fossils from the owls themselves, and even some turtles and crocodiles who might have fallen into the cave.”

In the empty tooth sockets of the mammal jaws, Dr. Viñola López and co-authors noticed that the sediment in these cavities didn’t look like it had just randomly accrued.

“It was a smooth surface, and almost concave. That’s not how sediment normally fills in, and I kept seeing it in multiple specimens. I was like, ‘Okay, there’s something weird here.’ It reminded me of the wasp nest,” Dr. Viñola López said.

Some of the more well-known nests built by bees and wasps belong to social species that live together and raise their young en masse in large colonies — think of paper wasp nests and the wax honeycombs in a honey bee nest.

“But actually, most bees are solitary. They lay their eggs in small cavities, and they leave pollen for the larvae to eat,” Dr. Viñola López said.

“Some bee species burrow holes in wood or in the ground, or use empty structures for nests. Some species in Europe and Africa even build their nests in empty snail shells.”

To better examine the potential insect nests present in the cave fossils, the authors CT scanned the bones, essentially X-raying the specimens from enough angles that they could produce 3D pictures of the compacted dirt inside the tooth sockets without destroying the fossils or disturbing the sediment.

The shapes and structures of the sediment looked just like the mud nests created by some bee species today; some of these nests even contained grains of ancient pollen that the bee mothers had sealed in the nests for their babies to eat.

They hypothesize that the bees mixed their saliva with dirt to make these little individual nests for their eggs; each nest was smaller than the eraser at the tip of a pencil.

Building their nests inside the bones of larger animals may have protected the bees’ eggs from hungry predators like wasps.

Since no bees were preserved, the researchers were not able to assign a species to the bees that made them.

However, the nests themselves were different enough from known bees’ nests that they were able to give a taxonomic classification to the fossil nests.

They classified the nests as Osnidum almontei after Juan Almonte Milan, the scientist who first discovered the cave.

“Since we didn’t find any of the bees’ bodies, it’s possible that they belonged to a species that’s still alive today — there’s very little known about the ecology of many of the bees on these islands,” Dr. Viñola López said.

The scientists suspect that this behavior was the result of several combined circumstances: there isn’t much soil covering the limestone ground in this region, so the bees may have turned to caves as a place to nest rather than simply burrowing in the ground like many other species.

And since this cave happened to be a multi-generational home for owls who coughed up a lot of owl pellets over the years, the bees took advantage of the bones delivered by the owls.

“This discovery shows how weird bees can be — they can surprise you. But it also shows that when you’re looking at fossils, you have to be very careful,” Dr. Viñola López said.

The paper was published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

_____

Lázaro W. Viñola-López et al. 2025. Trace fossils within mammal remains reveal novel bee nesting behaviour. R Soc Open Sci 12 (12): 251748; doi: 10.1098/rsos.251748