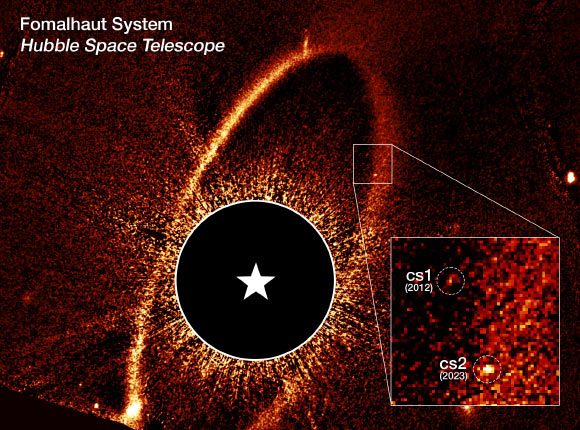

Fomalhaut — the 18th brightest star visible in night sky — is orbited by a compact source, Fomalhaut b, which has previously been interpreted as either a dust-enshrouded exoplanet or a dust cloud generated by the collision of two planetesimals. Such collisions are rarely observed but their debris can appear in direct imaging. The new observations with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope show the appearance in 2023 of a second point source around Fomalhaut, resembling the appearance of Fomalhaut b twenty years earlier. University of California, Berkeley astronomer Paul Kalas and his colleagues interpret this additional source as a dust cloud produced by a recent impact between two planetesimals.

This Hubble image shows the debris ring and dust clouds cs1 and cs2 around Fomalhaut. Image credit: NASA / ESA / P. Kalas, UC Berkeley / J. DePasquale, STScI.

Fomalhaut is an A-type star located just 25 light-years away in the constellation of Piscis Austrinus.

The name Fomalhaut derives from the Arabic name for this star — Fum al Hut, meaning ‘the Fish’s Mouth.’

The star is twice as massive as the Sun and 20 times brighter and is surrounded by a ring of dust and debris.

In 2008, astronomers used Hubble to discover a candidate planet around Fomalhaut, making it the first stellar system with a possible planet found using visible light.

That object, called Fomalhaut b, now appears to be a dust cloud masquerading as a planet — the result of colliding planetesimals.

While searching for Fomalhaut b in recent Hubble observations, Dr. Kalas and co-authors were surprised to find a second point of light at a similar location around the star.

They call this object circumstellar source 2 (cs2), while the first object is now known as cs1.

“This is certainly the first time I’ve ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system,” Dr. Kalas said.

“It’s absent in all of our previous Hubble images, which means that we just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge debris cloud unlike anything in our own Solar System today. Amazing!”

Why astronomers are seeing both of these debris clouds so physically close to each other is a mystery.

If the collisions between asteroids and planetesimals were random, cs1 and cs2 should appear by chance at unrelated locations.

Yet, they are positioned intriguingly near each other along the inner portion of Fomalhaut’s outer debris disk.

Another mystery is why scientists have witnessed these two events within such a short timeframe.

“Previous theory suggested that there should be one collision every 100,000 years, or longer. Here, in 20 years, we’ve seen two,” Dr. Kalas said.

“If you had a movie of the last 3,000 years, and it was sped up so that every year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes you’d see over that time.”

“Fomalhaut’s planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions.”

Collisions are fundamental to the evolution of planetary systems, but they are rare and difficult to study.

“The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows researchers to estimate both the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them there are in the disk, information which is almost impossible to get by any other means,” said Dr. Mark Wyatt, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge.

“Our estimates put the planetesimals that were destroyed to create cs1 and cs2 at just 30 km in size, and we infer that there are 300 million such objects orbiting in the Fomalhaut system.”

“The system is a natural laboratory to probe how planetesimals behave when undergoing collisions, which in turn tells us about what they are made of and how they formed.”

The results appear this week in the journal Science.

_____

Paul Kalas et al. 2025. A second planetesimal collision in the Fomalhaut system. Science, published online December 18, 2025; doi: 10.1126/science.adu6266