The data from NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn initially led researchers to suspect a large underground ocean composed of liquid water on Titan. However, when University of Washington scientist Baptiste Journaux and colleagues modeled the moon with an ocean, the results didn’t match the physical properties described by the data. Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers.

This composite image shows an infrared view of Titan. In this image blue represents wavelengths centered at 1.3 microns, green represents 2.0 microns, and red represents 5.0 microns. A view at visible wavelengths would show only Titan’s hazy atmosphere; the near-infrared wavelengths in this image allow Cassini’s vision to penetrate the haze and reveal the moon’s surface. The view looks toward terrain that is mostly on the Saturn-facing hemisphere of Titan. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute.

The Cassini mission, which began in 1997 and lasted nearly 20 years, produced volumes of data about Saturn and its 274 moons.

Titan is the only world, apart from Earth, known to have liquid on its surface.

Temperatures hover around minus 183 degrees Celsius (minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit). Instead of water, liquid methane forms lakes and falls as rain.

As Titan circled Saturn in an elliptical orbit, scientists observed the moon stretching and smushing depending on where it was in relation to Saturn.

In 2008, they proposed that Titan must possess a huge ocean beneath the surface to allow such significant deformation.

“The degree of deformation depends on Titan’s interior structure,” Dr. Journaux said.

“A deep ocean would permit the crust to flex more under Saturn’s gravitational pull, but if Titan were entirely frozen, it wouldn’t deform as much.”

“The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean, but now we know that isn’t the full story.”

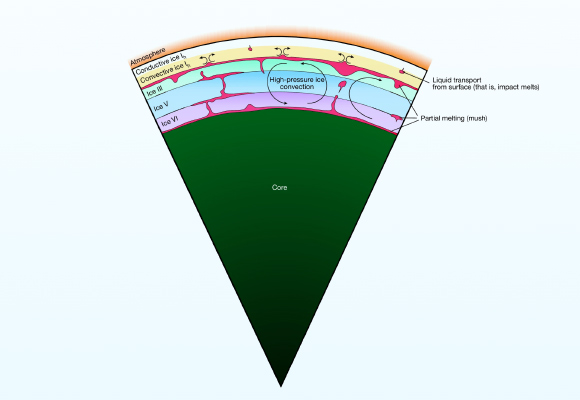

Schematic interior structure of Titan revealed by Petricca et al. Image credit: Petricca et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09818-x.

In the new study, Dr. Journaux and co-authors introduce a new level of subtlety: timing.

Titan’s shape shifting lags about 15 hours behind the peak of Saturn’s gravitational pull.

Like a spoon stirring honey, it takes more energy to move a thick, viscous substance than liquid water.

Measuring the delay told scientists how much energy it takes to change Titan’s shape, allowing them to make inferences about the viscosity of the interior.

The amount of energy lost, or dissipated, in Titan was much greater than the researchers expected to see in the global ocean scenario.

“Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan,” said Dr. Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses.”

The model the scientists propose instead features more slush and quite a bit less liquid water.

Slush is thick enough to explain the lag but still contains water, enabling Titan to morph when tugged.

“The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes,” Dr. Journaux said.

“Water and ice behave in a different way than sea water here on Earth.”

The study was published today in the journal Nature.

_____

F. Petricca et al. 2025. Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean. Nature 648, 556-561; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09818-x