New research shows that Phaethon’s comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust.

This illustration depicts the asteroid Phaethon being heated by the Sun. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / IPAC.

Also known as 1983 TB, Phaethon was discovered on October 11, 1983 by astronomers Simon Green and John Davies in data from NASA’s Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS).

With a diameter of about 3.2 miles (5.1 km), this asteroid is the third largest near-Earth asteroid classified as ‘potentially hazardous’ after asteroids (53319) 1999 JM8 and 4183 Cuno.

Phaethon is the parent body of the Geminid meteor shower of mid-December.

It is categorized as a so-called Apollo asteroid, as its orbital semi-major axis is greater than that of the Earth’s at 118 million miles (190 million km, or 1.27 AU).

In 2009, NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spotted a short tail extending from Phaethon as the asteroid reached its closest point to the Sun — or perihelion — along its 524-day orbit.

Regular telescopes hadn’t seen the tail before because it only forms when Phaethon is too close to the Sun to observe, except with solar observatories.

STEREO also saw Phaethon’s tail develop on later solar approaches in 2012 and 2016.

The tail’s appearance supported the idea that dust was escaping the asteroid’s surface when heated by the Sun.

However, in 2018, observations from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe showed that the trail contained far more material than Phaethon could possibly shed during its close approaches to the Sun.

California Institute of Technology Ph.D. student Qicheng Zhang and colleagues wondered whether something else, other than dust, was behind Phaethon’s comet-like behavior.

“Comets often glow brilliantly by sodium emission when very near the Sun, so we suspected sodium could likewise serve a key role in Phaethon’s brightening,” Zhang said.

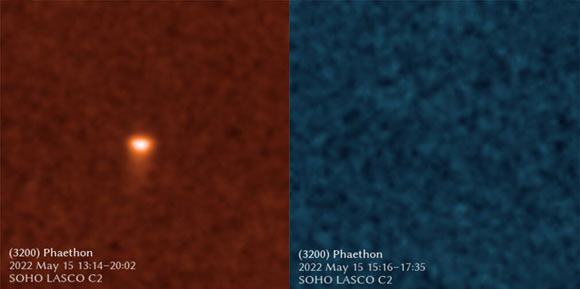

The Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on the NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) imaged asteroid Phaethon through different filters as the asteroid passed near the Sun in May 2022. On the left, the sodium-sensitive orange filter shows the asteroid with a surrounding cloud and small tail, suggesting that sodium atoms from the asteroid’s surface are glowing in response to sunlight. On the right, the dust-sensitive blue filter shows no sign of Phaethon, indicating that the asteroid is not producing any detectable dust. Image credit: NASA / ESA / Qicheng Zhang.

An earlier study, based on models and lab tests, suggested that the Sun’s intense heat during Phaethon’s close solar approaches could indeed vaporize sodium within the asteroid and drive comet-like activity.

Hoping to find out what the tail is really made of, Zhang and co-authors looked for it again during Phaethon’s latest perihelion in 2022.

They used the NASA/ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft, which has color filters that can detect sodium and dust.

They also searched archival images from STEREO and SOHO, finding the tail during 18 of Phaethon’s close solar approaches between 1997 and 2022.

In SOHO’s observations, the asteroid’s tail appeared bright in the filter that detects sodium, but it did not appear in the filter that detects dust.

In addition, the shape of the tail and the way it brightened as Phaethon passed the Sun matched exactly what scientists would expect if it were made of sodium, but not if it were made of dust.

This evidence indicates that Phaethon’s tail is made of sodium, not dust.

“Not only do we have a really cool result that kind of upends 14 years of thinking about a well-scrutinized object,” said Dr. Karl Battams, an astronomer at the Naval Research Laboratory.

“But we also did this using data from two heliophysics spacecraft — SOHO and STEREO — that were not at all intended to study phenomena like this.”

The study authors now wonder whether some comets discovered by SOHO — and by citizen scientists studying SOHO images as part of the Sungrazer Project — are not comets at all.

“A lot of those other sunskirting ‘comets’ may also not be ‘comets’ in the usual, icy body sense, but may instead be rocky asteroids like Phaethon heated up by the Sun,” Zhang said.

Still, one important question remains: if Phaethon doesn’t shed much dust, how does the asteroid supply the material for the Geminid meteor shower we see each December?

“We suspect that some sort of disruptive event a few thousand years ago — perhaps a piece of the asteroid breaking apart under the stresses of Phaethon’s rotation — caused Phaethon to eject the billion tons of material estimated to make up the Geminid debris stream. But what that event was remains a mystery,” the astronomers said.

The study was published in the Planetary Science Journal.

_____

Qicheng Zhang et al. 2023. Sodium Brightening of (3200) Phaethon near Perihelion. Planet. Sci. J 4, 70; doi: 10.3847/PSJ/acc866