Supermassive black holes in the center of galaxy clusters usually suppress star formation, but the one in the Phoenix Cluster, a group of about 1,000 galaxies located about 5.8 billion light-years from Earth in the constellation of Phoenix, is not; in his unique galaxy cluster, the jets from the central black hole appear to be aiding in the formation of stars.

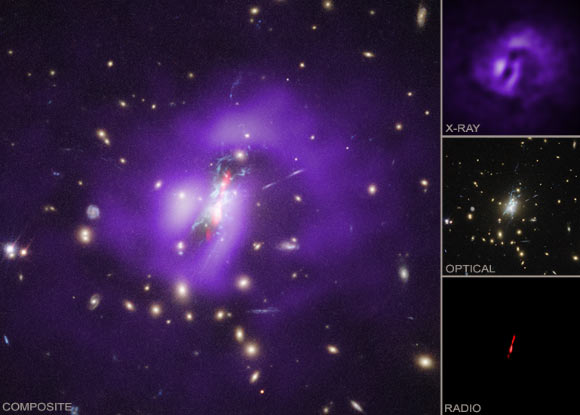

This image of the Phoenix Cluster combines X-ray, radio and optical data; side panels show the individual images making up the composite. Image credit: NASA / CXC / MIT / M. McDonald et al / NRAO / AUI / NSF / STScI.

“This is a phenomenon that we had been trying to find for a long time,” said MIT astronomer Dr. Michael McDonald, lead author of the study published in the Astrophysical Journal.

“The Phoenix Cluster demonstrates that, in some instances, the energetic output from a black hole can actually enhance cooling, leading to dramatic consequences.”

At the center of the Phoenix Cluster lies a massive galaxy, which appears to be spitting out stars at a huge rate.

The galaxy is surrounded by hot gas with temperatures of millions of degrees. The mass of this gas, equivalent to trillions of Suns, is several times greater than the combined mass of all the galaxies in the cluster.

This hot gas loses energy as it glows in X-rays, which should cause it to cool until it can form large numbers of stars. However, in all other observed galaxy clusters, bursts of energy driven by such a black hole keep most of the hot gas from cooling, preventing widespread star birth.

“Imagine running an air-conditioner in your house on a hot day, but then starting a wood fire. Your living room can’t properly cool down until you put out the fire,” said co-author Dr. Brian McNamara, an astronomer at the University of Waterloo.

“Similarly, when a black hole’s heating ability is turned off in a galaxy cluster, the gas can then cool.”

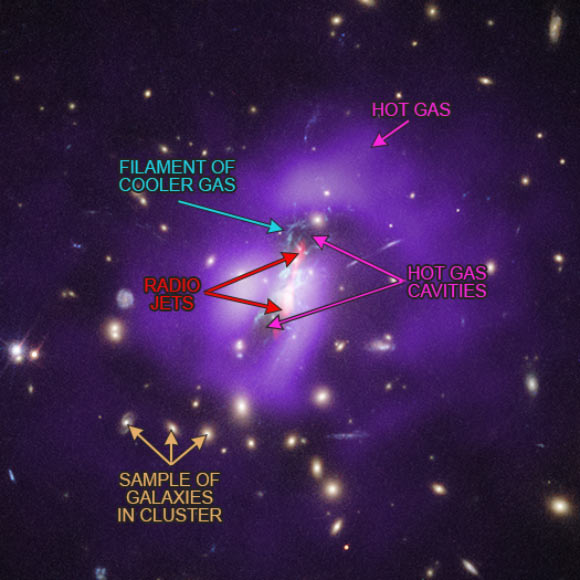

Combined X-ray, optical and radio image reveals the mechanism allowing rapid star formation at the core of the Phoenix Cluster. Image credit: NASA / CXC / MIT / M. McDonald et al / NRAO / AUI / NSF / STScI.

Evidence for rapid star formation in the Phoenix Cluster was previously reported in 2012.

But deeper observations were required to learn details about the central black hole’s role in the rebirth of stars in the central galaxy, and how that might change in the future.

Using observations from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and NSF’s Karl Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), Dr. McDonald, Dr. McNamara and their colleagues gained a ten-fold improvement in the data quality compared to previous observations.

The Chandra data reveal that hot gas is cooling nearly at the rate expected in the absence of energy injected by a black hole.

The Hubble data show that about 10 billion solar masses of cool gas are located along filaments leading towards the black hole, and young stars are forming from this cool gas at a rate of about 500 solar masses per year. By comparison, stars are forming in the Milky Way Galaxy at a rate of about one solar mass per year.

The VLA radio data reveal jets blasting out from the vicinity of the central black hole.

These jets likely inflated bubbles in the hot gas that are detected in the Chandra data.

Both the jets and bubbles are evidence of past rapid growth of the black hole.

Early in this growth, the black hole may have been undersized, compared to the mass of its host galaxy, which would allow rapid cooling to go unchecked.

“In the past, outbursts from the undersized black hole may have simply been too weak to heat its surroundings, allowing hot gas to start cooling,” said co-author Dr. Matthew Bayliss, from the University of Cincinnati.

“But as the black hole has grown more massive and more powerful, its influence has been increasing.”

The cooling can continue when the gas is carried away from the center of the cluster by the black hole’s outbursts. At a greater distance from the heating influence of the black hole, the gas cools faster than it can fall back towards the center of the cluster.

This scenario explains the observation that cool gas is located around the borders of the cavities, based on a comparison of the Chandra and Hubble data.

Eventually the outburst will generate enough turbulence, sound waves and shock waves to provide sources of heat and prevent further cooling. This will continue until the outburst ceases and the build-up of cool gas can recommence. The whole cycle may then repeat.

“These results show that the black hole has temporarily been assisting in the formation of stars, but when it strengthens its effects will start to mimic those of black holes in other clusters, stifling more star birth,” said co-author Dr. Mark Voit, from Michigan State University.

The lack of similar objects shows that clusters and their enormous black holes pass through the rapid star formation phase relatively quickly.

_____

M. McDonald et al. 2019. Anatomy of a Cooling Flow: The Feedback Response to Pure Cooling in the Core of the Phoenix Cluster. ApJ 885, 63; doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab464c