A team of scientists from the University of Queensland and King’s College London has found that the venom of Australian Dendrocnide trees contains previously unidentified neurotoxic peptides and that the 3D structure of these pain-inducing peptides is reminiscent of spider and cone snail venoms targeting the same pain receptors, thus representing a remarkable case of inter-kingdom convergent evolution of animal and plant venoms.

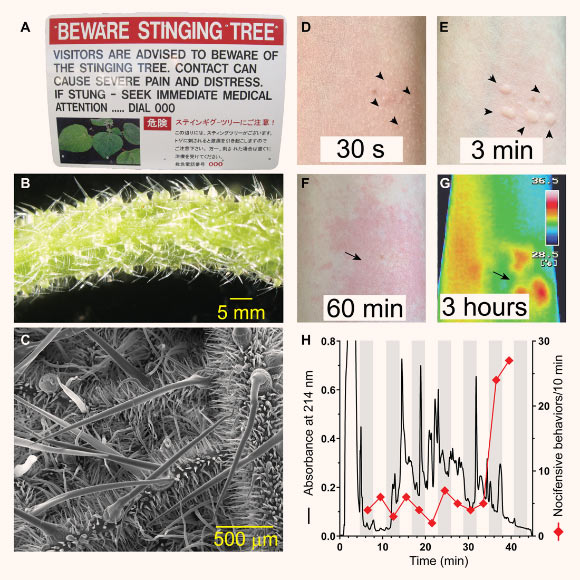

Stinging nettles of the genus Dendrocnide produce potent neurotoxins: (A) sign at a North Queensland National Park advising caution around stinging trees; (B) Dendrocnide excelsa petioles are covered in stinging hairs; (C) scanning electron micrograph of trichome structure on the leaf of Dendrocnide moroides; (D-G) cutaneous reaction resulting from an accidental sting with Dendrocnide moroides documented with an iPhone XR and NEC G120W2 thermal imager, illustrating almost immediate local piloerection (arrowheads in D), development of wheals where stinging hairs penetrate the skin (arrows in E), as well as a long-lasting axon reflex erythema (arrows in F and G) and associated local increase in skin temperature (degrees Celsius); (H) HPLC chromatogram of trichome extract from Dendrocnide excelsa; diamonds indicate nocifensive responses elicited by intraplantar administration of individual fractions in vivo in C57BL6/J mice, with a single late-eluting peak identified as the main pain-causing fraction. Image credit: Irina Vetter, Thomas Durek & Darren Brown, University of Queensland.

Australia notoriously harbors some of the world’s most venomous animals, but although less well known, its venomous flora is equally remarkable.

The giant stinging tree (Dendrocnide excelsa) reigns superlative in size, with some specimens growing to 35 m (115 feet) tall along the slopes and gullies of eastern Australian rainforests. However, these members of the family Urticaceae are far more than oversized nettles.

Of the six species in the genus Dendrocnide native to the subtropical and tropical forests of Eastern Australia, the giant stinging tree and the mulberry-like stinging tree (Dendrocnide moroides) are particularly notorious for producing painful stings, which can cause symptoms that last for days or weeks in extreme cases.

“Like other stinging plants such as nettles, the giant stinging tree is covered in needle-like appendages called trichomes that are around five millimeters in length — the trichomes look like fine hairs, but actually act like hypodermic needles that inject toxins when they make contact with skin,” said Dr. Irina Vetter, a researcher in the Institute for Molecular Bioscience and the School of Pharmacy at the University of Queensland.

Small molecules in the trichomes such as histamine, acetylcholine and formic acid have been previously tested, but injecting these did not cause the severe and long-lasting pain of the stinging tree, suggesting that there was an unidentified neurotoxin to be found.

“We were interested in finding out if there were any neurotoxins that could explain these symptoms, and why the Gympie-Gympie can cause such long-lasting pain,” Dr. Vetter said.

The scientists found a completely new class of neurotoxin miniproteins that they termed ‘gympietides,’ after the Indigenous name for the plant.

“Although they come from a plant, the gympietides are similar to spider and cone snail toxins in the way they fold into their 3D molecular structures and target the same pain receptors — this arguably makes the Gympie-Gympie tree a truly ‘venomous’ plant,” Dr. Vetter said.

“The long-lasting pain from the stinging tree may be explained by the gympietides permanently changing the sodium channels in the sensory neurons, not due to the fine hairs getting stuck in the skin.”

“By understanding how this toxin works, we hope to provide better treatment to those who have been stung by the plant, to ease or eliminate the pain.”

“We can also potentially use the gympietides as scaffolds for new therapeutics for pain relief.”

The findings were published online in the journal Science Advances.

_____

Edward K. Gilding et al. 2020. Neurotoxic peptides from the venom of the giant Australian stinging tree. Science Advances 6 (38): eabb8828; doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb8828