A new species of marine predator that lived about 506 million years ago (Cambrian period) has been identified from exceptionally well-preserved fossils found in Kootenay National Park — part of the famous Burgess Shale Formation — in Canada.

Named Cambroraster falcatus, the ancient creature was up to one foot (30 cm) in length.

“Its size would have been even more impressive at the time it was alive, as most animals living during the Cambrian Period were smaller than your little finger,” said Joe Moysiuk, a graduate student at the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum.

“Cambroraster falcatus was a distant cousin of Anomalocaris, the top predator living in the seas at that time, but it seems to have been feeding in a radically different way.”

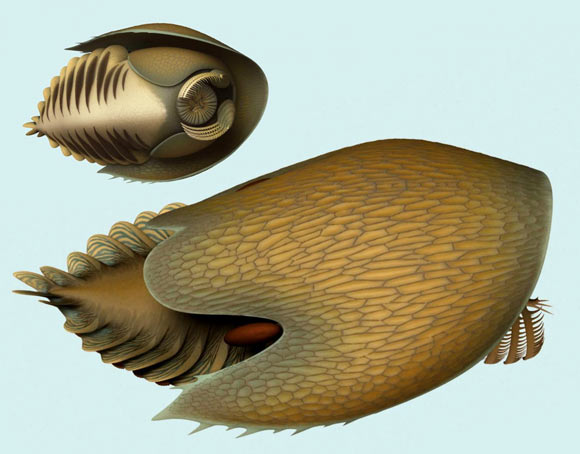

The animal had a large horseshoe-shaped head carapace, rake-like claws and a pineapple-slice-shaped mouth.

“We think Cambroraster falcatus may have used these claws to sift through sediment, trapping buried prey in the net-like array of hooked spines,” said Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, also from the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum.

“With the interspace between the spines on the claws at typically less than a millimeter, this would have enabled the animal to feed on very small organisms, although larger prey could also likely be captured, and ingested into the circular tooth-lined mouth.”

This specialized mouth apparatus is the namesake of the extinct group Radiodonta, which includes both Cambroraster falcatus and Anomalocaris and is considered to be one of the earliest offshoots of the arthropod lineage.

“With its broad head carapace with deep notches accommodating the upward facing eyes, Cambroraster falcatus resembles modern living bottom-dwelling animals like horseshoe crabs,” Moysiuk said.

“This represents a remarkable case of evolutionary convergence in these radiodonts.”

“Such convergence is likely reflective of a similar environment and mode of life — like modern horseshoe crabs, Cambroraster falcatus may have used its carapace to plough through sediment as it fed.”

Perhaps even more astonishing is the large number of specimens recovered.

“The sheer abundance of this animal is extraordinary,” Dr. Caron said.

Based on over a hundred exceptionally well-preserved fossils, the team was able to reconstruct Cambroraster falcatus in unprecedented detail, revealing characteristics that had not been seen before in related species.

“The radiodont fossil record is very sparse; typically, we only find scattered bits and pieces. The large number of parts and unusually complete fossils preserved at the same place are a real coup, as they help us to better understand what these animals looked like and how they lived,” Dr. Caron said.

“We are really excited about this discovery. Cambroraster falcatus clearly illustrates that predation was a big deal at that time with many kinds of surprising morphological adaptations.”

A paper describing Cambroraster falcatus was published online this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

_____

J. Moysiuk & J.-B. Caron. 2019. A new hurdiid radiodont from the Burgess Shale evinces the exploitation of Cambrian infaunal food sources. Proc. R. Soc. B 286 (1908); doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1079