Paleontologists from the American Museum of Natural History have described a shark species that lived during Carboniferous period, about 325 million years ago. The analysis of its fossilized skull shows that living sharks are actually quite advanced in evolutionary terms, despite having retained their basic ‘sharkiness’ over millions of years.

The exceptionally well-preserved fossil of Ozarcus mapesae from two different lateral views. Scale bar is 1 cm. Image credit: © AMNH / F. Ippolito.

“Sharks are traditionally thought to be one of the most primitive surviving jawed vertebrates. And most textbooks in schools today say that the internal jaw structures of modern sharks should look very similar to those in primitive shark-like fishes. But we’ve found that’s not the case. The modern shark condition is very specialized, very derived, and not primitive,” said Dr Alan Pradel, who is the lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

The well-preserved shark fossil has been found by Ohio University scientists in Arkansas, where an ocean basin once was home to a diverse marine ecosystem, and described as the new species, Ozarcus mapesae.

The heads of all fishes – sharks included – are segmented into the jaws and a series of arches that support the jaw and the gills. These arches are thought to have given rise to jaws early in the tree of life. Because shark skeletons are made of cartilage, not bone, their fossils are very fragile and are usually found in flattened fragments, making it impossible to study the shape of these internal structures. But the Ozarcus mapesae specimen was preserved in a nearly 3D state, giving the paleontologists a rare glimpse at the organization of the arches in a prehistoric animal.

“This beautiful fossil offers one of the first complete looks at all of the gill arches and associated structures in an early shark. There are other shark fossils like this in existence, but this is the oldest one in which you can see everything. There’s enough depth in this fossil to allow us to scan it and digitally dissect out the cartilage skeleton,” said study co-author Dr John Maisey.

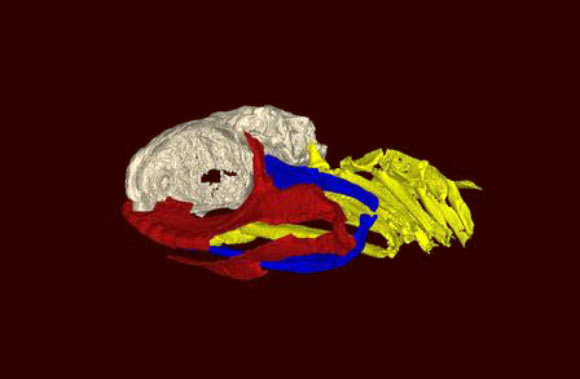

A 3D reconstruction of the skull of Ozarcus mapesae. The braincase is shown in light grey, the jaw is shown in red, the hyoid arch is shown in blue, and the gill arches are shown in yellow. Image credit: © AMNH / A. Pradel.

The team imaged the Ozarcus mapesae fossil with high-resolution X-rays to get a detailed view of each individual arch shape and organization.

“We discovered that the arrangement of the arches is not like anything you’d see in a modern shark or shark-like fish. Instead, the arrangement is fundamentally the same as bony fishes,” Dr Pradel said.

“It’s not unexpected that sharks – which have existed for about 420 million years – would undergo evolution of these structures. But the new work, especially when considered alongside other recent developments about early jawed vertebrates, has significant implications for the future of evolutionary studies of this group.”

Dr Maisey added: “bony fishes might have more to tell us about our first jawed ancestors than do living sharks.”

______

Alan Pradel et al. A Palaeozoic shark with osteichthyan-like branchial arches. Nature, published online April 16, 2014; doi: 10.1038/nature13195