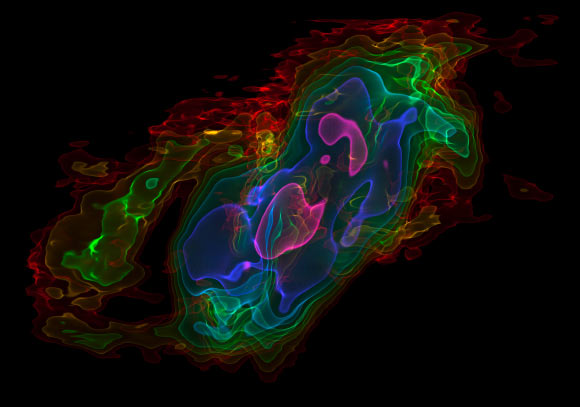

Very detailed new observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) of nearby starburst galaxy NGC 253 may help explain the strange paucity of very massive galaxies in the Universe.

This is a 3D visualization of ALMA observations of cold carbon monoxide gas in the nearby starburst galaxy NGC 253 (ALMA / ESO / NAOJ / NRAO / Erik Rosolowsky)

Galaxies are the basic building blocks of the cosmos. One ambitious goal of contemporary astronomy is to understand the ways in which galaxies grow and evolve, a key question being star formation: what determines the number of new stars that will form in a galaxy?

NGC 253, also known the Silver Dollar Galaxy or the Sculptor Galaxy, is a spiral galaxy located in the constellation of Sculptor at a distance of about 11.5 million light-years. It is one of our closer intergalactic neighbors and one of the closest starburst galaxies visible from the southern hemisphere.

The new observations, reported in the journal Nature, reveal billowing columns of cold, dense gas fleeing the disk of NGC 253.

“With ALMA’s superb resolution and sensitivity, we can clearly see for the first time massive concentrations of cold gas being jettisoned by expanding shells of intense pressure created by young stars,” said study lead author Dr Alberto Bolatto of the University of Maryland.

“The amount of gas we measure gives us very good evidence that some growing galaxies spew out more gas than they take in. We may be seeing a present-day example of a very common occurrence in the early Universe.”

These results may help explain why astronomers have found surprisingly few high-mass galaxies throughout the cosmos.

Computer models show that older galaxies should have considerably more mass and a larger number of stars than we currently observe. It seems that the galactic winds or outflow of gas are so strong that they deprive the galaxy of the fuel for the formation of the next generation of stars.

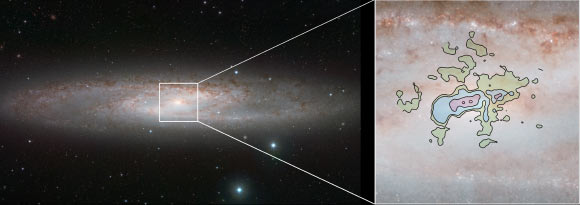

This picture shows the infrared view of NGC 253 from ESO’s VISTA Telescope and a detailed new view of the cool gas outflows at millimeter wavelengths from ALMA (ESO / ALMA / NAOJ / NRAO / J. Emerson / VISTA / Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit)

“These features trace an arc that is almost perfectly aligned with the edges of the previously observed hot, ionized gas outflow. We can now see the step-by-step progression of starburst to outflow,” said co-author Dr Fabian Walter of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

Dr Bolatto and his colleagues determined that vast quantities of molecular gas – nearly ten times the mass of our Sun each year – were being ejected from NGC 253 at velocities between 150 thousand and almost 1 million km per hour.

The total amount of gas ejected would add up to more gas than actually went into forming the galaxy’s stars in the same time. At this rate, the galaxy could run out of gas in as few as 60 million years.

“More studies with the full ALMA array will help us figure out the ultimate fate of the gas carried away by the wind. This will help us understand whether these starburst-driven winds recycle or truly remove star forming material,” said co-author Dr Adam Leroy from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia.

______

Bibliographic information: Alberto D. Bolatto et al. 2013. Suppression of star formation in the galaxy NGC 253 by a starburst-driven molecular wind. Nature, 499, pp. 450–453; doi: 10.1038/nature12351