NASA’s SPHEREx (Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer) space telescope has completed its first infrared map of the entire sky in 102 colors using observations made between May and December 2025. While not visible to the human eye, these 102 infrared wavelengths of light are prevalent in the cosmos, and observing the entire sky this way enables scientists to answer big questions, including how a dramatic event that occurred in the first billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang influenced the 3D distribution of hundreds of millions of galaxies in our Universe. In addition, they will use the data to study how galaxies have changed over the Universe’s 13.8 billion-year history and learn about the distribution of key ingredients for life in our own Milky Way Galaxy.

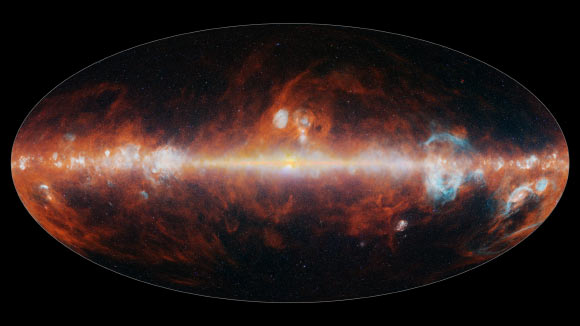

This infrared image from SPHEREx features a selection of colors emitted primarily by stars (blue, green, and white), hot hydrogen gas (blue), and cosmic dust (red). Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech.

Circling Earth about 14.5 times a day, SPHEREx travels from north to south, passing over the poles.

Each day it takes about 3,600 images along one circular strip of the sky, and as the days pass and the planet moves around the Sun, SPHEREx’s field of view shifts as well.

After six months, the observatory has looked out into space in every direction, capturing the entire sky in 360 degrees.

Managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, the mission began mapping the sky in May and completed its first all-sky mosaic in December.

It will complete three additional all-sky scans during its two-year primary mission, and merging those maps together will increase the sensitivity of the measurements.

“It’s incredible how much information SPHEREx has collected in just six months — information that will be especially valuable when used alongside our other missions’ data to better understand our Universe,” said Dr. Shawn Domagal-Goldman, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters.

“We essentially have 102 new maps of the entire sky, each one in a different wavelength and containing unique information about the objects it sees.”

“I think every astronomer is going to find something of value here, as NASA’s missions enable the world to answer fundamental questions about how the universe got its start, and how it changed to eventually create a home for us in it.”

“SPHEREx is a mid-sized astrophysics mission delivering big science,” said Dave Gallagher, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“It’s a phenomenal example of how we turn bold ideas into reality, and in doing so, unlock enormous potential for discovery.”

Each of the 102 colors detected by SPHEREx represents a wavelength of infrared light, and each wavelength provides unique information about the galaxies, stars, planet-forming regions, and other cosmic features therein.

For example, dense clouds of dust in our Galaxy where stars and planets form radiate brightly in certain wavelengths but emit no light (and are therefore totally invisible) in others.

The process of separating the light from a source into its component wavelengths is called spectroscopy.

And while a handful of previous missions has also mapped the entire sky, such as NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, none have done so in nearly as many colors as SPHEREx.

By contrast, the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope can do spectroscopy with significantly more wavelengths of light than SPHEREx, but with a field of view thousands of times smaller.

The combination of colors and such a wide field of view is why SPHEREx is so powerful.

“The superpower of SPHEREx is that it captures the whole sky in 102 colors about every six months,” said SPHEREx project manager Dr. Beth Fabinsky, also of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“That’s an amazing amount of information to gather in a short amount of time.”

“I think this makes us the mantis shrimp of telescopes, because we have an amazing multicolor visual detection system and we can also see a very wide swath of our surroundings.”