Paleontologists have found a well-preserved fossil of a megacheiran – distant relative of scorpions and spiders – that lived in Cambrian seas about 520 million years ago. The fossil creature, named Alalcomenaeus, is the earliest known to show complete nervous system.

Collected from the famous Chengjiang formation near Kunming in southwest China, the four-eyed, 3-cm-long Alalcomenaeus belongs to an extinct group of marine arthropods known as megacheirans (large claws in Greek).

These animals had an elongated, segmented body equipped with about a dozen pairs of body appendages enabling the animal to swim or crawl or both. All featured a pair of long, scissor-like appendages attached to the head, most likely for grasping or sensory purposes.

Alalcomenaeus solves the long-standing mystery of where this group fits in the tree of life. It suggests that the ancestors of spiders, scorpions and their kin (chelicerates) branched off from the family tree of other arthropods – including insects, crustaceans and millipedes – more than half a billion years ago.

“We now know that the megacheirans had central nervous systems very similar to today’s horseshoe crabs and scorpions. This means the ancestors of spiders and their kin lived side by side with the ancestors of crustaceans in the Lower Cambrian,” said Prof Nick Strausfeld from the University of Arizona, who is a senior author of a paper published in the journal Nature.

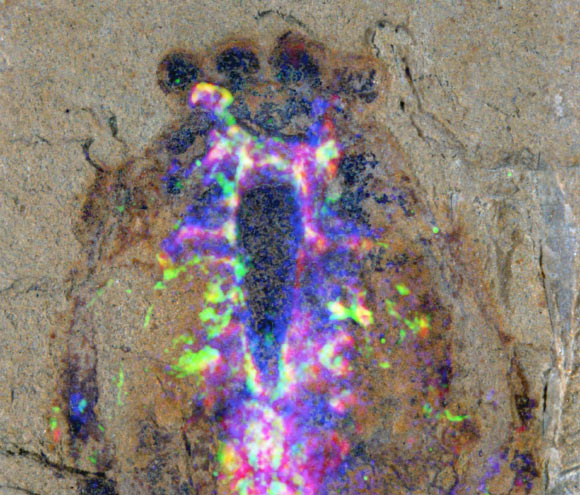

Prof Strausfeld’s team analyzed the fossil by applying different imaging and image processing techniques, taking advantage of iron deposits that had selectively accumulated in the nervous system during fossilization.

A close-up of the head region of the Alalcomenaeus reveals the distribution of chemical elements in the fossil: copper shows up as blue, iron as magenta and the computed tomography scans as green; the coincidence of iron and computed tomography denote nervous system. Image credit: N. Strausfeld / University of Arizona.

“Some paleontologists had used the external appearance of the so-called great appendage to infer that the megacheirans were related to chelicerates, based on the fact that the great appendage and the fangs of a spider or scorpion both have an elbow joint between their basal part and their pincer-like tip,” added study co-author Dr Greg Edgecombe from Natural History Museum in London, UK.

“However, this wasn’t rock solid because others lined up the great appendage either a segment in front of spider fangs or one segment behind them.”

“We have now managed to add direct evidence from which segment the brain sends nerves into the great appendage. It’s the second one, the same as in the fangs, or chelicerae.”

“For the first time we can analyze how the segments of these fossil arthropods line up with each other the same way as we do with living species – using their nervous systems.”

______

Bibliographic information: Gengo Tanaka et al. 2013. Chelicerate neural ground pattern in a Cambrian great appendage arthropod. Nature 502, pp. 364–367; doi: 10.1038/nature12520