New state-of-the-art simulations by Maynooth University astronomers show that in the dense, turbulent dawn of the cosmos, ‘light seed’ black holes could rapidly swallow matter and rival the colossal black holes seen in the center of early galaxies.

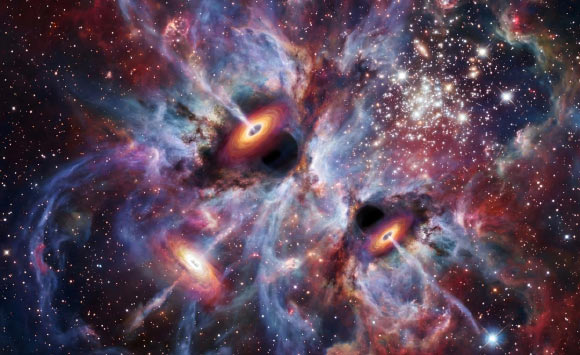

Computer visualization showing baby black holes growing in a young galaxy in the early Universe. Image credit: Maynooth University.

“We found that the chaotic conditions that existed in the early Universe triggered early, smaller black holes to grow into the supermassive black holes we see later following a feeding frenzy which devoured material all around them,” said Daxal Mehta, a Ph.D. candidate at Maynooth University.

“We revealed, using state-of-the-art computer simulations, that the first generation of black holes — those born just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang — grew incredibly fast, into tens of thousands of times the size of our Sun.”

“This breakthrough unlocks one of astronomy’s big puzzles,” said Dr. Lewis Prole, a postdoctoral researcher at Maynooth University.

“That being how black holes born in the early Universe, as observed by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, managed to reach such supermassive sizes so quickly.”

The dense, gas-rich environments in early galaxies enabled short bursts of ‘super Eddington accretion’; a term used to describe what happens when a black hole ‘eats’ matter faster than what’s normal or safe.

So fast, that it should blow its food away with light but somehow keeps eating it anyway.

The results provided a ‘missing link’ between the first stars and the supermassive black holes that came much later.

“These tiny black holes were previously thought to be too small to grow into the behemoth black holes observed at the center of early galaxies,” Mehta said.

“What we have shown here is that these early black holes, while small, are capable of growing spectacularly fast, given the right conditions.”

Black holes come in ‘heavy seed’ and ‘light seed’ types.

The light seed types are relatively small to begin with, only about ten to a few hundred times the mass of our Sun at most and must grow from there to become ‘supermassive’ — millions of times the mass of the Sun.

The heavy types on the other hand start life already much more massive, perhaps up to one hundred thousand times the mass of the Sun at birth.

Up to now, astronomers thought that heavy seed types were required to explain the presence of the supermassive black holes found to reside at the center of most large galaxies.

“Now we’re not so sure,” said Dr. John Regan, an astronomer at Maynooth University.

“Heavy seeds are somewhat more exotic and may need rare conditions to form.”

“Our simulations show that your ‘garden variety’ stellar mass black holes can grow at extreme rates in the early Universe.”

The research reshapes the understanding of black hole origins but also highlights the importance of high-resolution simulations in uncovering the Universe’s earliest secrets.

“The early Universe is much more chaotic and turbulent than we expected, with a much larger population of massive black holes than we anticipated too,” Dr. Regan said.

The results also have implications for the ESA/NASA Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission, scheduled to launch in 2035.

“Future gravitational wave observations from that mission may be able to detect the mergers of these tiny, early, rapidly growing baby black holes,” Dr. Regan said.

A paper on the findings was published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy.

_____

D.H. Mehta et al. The growth of light seed black holes in the early Universe. Nat Astron, published online January 21, 2026; doi: 10.1038/s41550-025-02767-5