Dr Bhuminder Singh from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and his colleagues have announced the discovery of a new mechanism for the development of cancer.

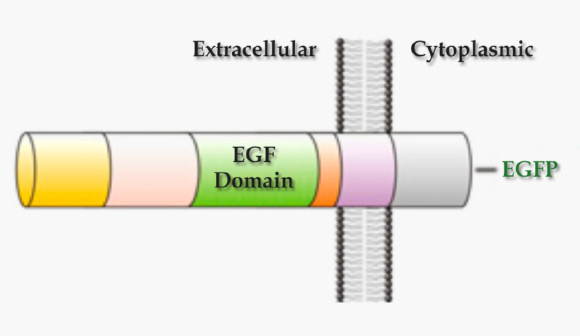

Domain organization of the human epidermal growth factor receptor ligand Epiregulin (Bhuminder Singh et al)

Their paper, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes how ‘mistrafficking’ of a ligand – a protein that binds to the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor – can ‘transform’ epithelial cells into a particularly vicious tumor in mice.

“Mutations that would cause mistrafficking of epiregulin have been found in human tumors. This supports the relevance of this work to the 90 percent of human cancers that arise from epithelial cells,” Dr Singh said.

Discovered about 60 years ago, EGF is not the only protein that binds to and activates the EGF receptor. There are actually seven different EGF receptor ligands, each of which has its own purpose in specific tissues at different times during development. The EGF receptor is thus a multipurpose signaling ‘switch.’

Epithelial cells are ‘polarized,’ meaning that they have one ‘apical’ surface that faces the lumen, or body cavities, lateral sides and a ‘basal,’ or bottom side. The basal and lateral, or basolateral, sides face inward, toward other cells, the blood or supportive tissue. Most EGF receptors are located on the basolateral surfaces of epithelial cells. But about 5 percent to 10 percent are also found on the apical surface.

Conventional scientific wisdom has held that these receptors don’t serve any important function. The team at Vanderbilt University Medical Center wasn’t so sure.

The scientists focused on epiregulin, which normally is expressed in low levels in normal epithelia. But when the epiregulin gene is overexpressed along with three other genes, cancer cells in the breast can break free and move, or metastasize, to the lung.

“Does epiregulin play a role in other cancers, too?” To answer that question, they turned their attention to the ligand’s cytoplasmic ‘tail,’ the specific sequence of amino acids that acts like a bar code – telling the cell where the ligand should be ‘delivered.’

In the kidney, for example, a rare, inherited genetic mutation that changes the EGF ‘barcode’ prevents it from being delivered to and activating the correct EGF receptor. That, in turn, blocks the kidney from absorbing magnesium, and causes a potentially life-threatening condition.

“What would happen in polarized epithelial cells if epiregulin’s barcode was altered?” Dr Singh found, that by switching a single amino acid, he could redirect epiregulin from its normal basolateral destination to the apical surface. When, in a mouse model, epiregulin bound with the small number of EGF receptors there, it triggered massive transformation – cancer.

“Previously if you would have seen this mutation, you would say that it’s inconsequential,” Dr Singh said. “But our study tells you that location of ligands in the cell is crucial.”

______

Bibliographic information: Bhuminder Singh et al. Transformation of polarized epithelial cells by apical mistrafficking of epiregulin. PNAS, published online May 13, 2013; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305508110