New observations of the young cluster SPT2349-56 with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have revealed unexpectedly scorching intracluster gas just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, challenging current models of galaxy cluster evolution.

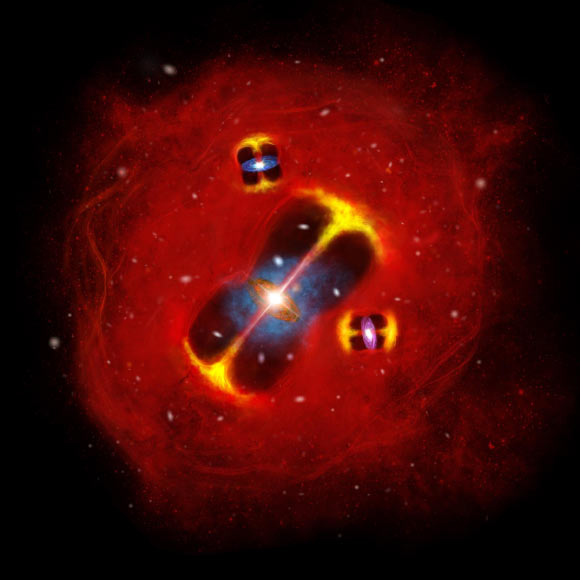

An artist’s impression of the forming galaxy cluster SPT2349-56: radio jets from active galaxies embedded in a hot intracluster atmosphere (red), illustrating a large thermal reservoir of gas in the nascent cluster. Image credit: Lingxiao Yuan.

SPT2349-56 is located approximately 12.4 billion light-years away, meaning its light started traveling to us when the Universe was only 1.4 billion years old, or about a tenth of its present age.

The protocluster’s compact core hosts several actively growing supermassive black holes and more than 30 starburst galaxies.

The galaxies are forming stars as much as 1,000 times faster than our Milky Way Galaxy and are crammed inside a region of space only about three times the size of the Milky Way.

“We didn’t expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” said Dazhi Zhou, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia.

The astronomers used an unusual observation technique called the thermal Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (tSZ) effect.

Rather than looking for light from the gas itself, this effect reveals a small shadow cast by hot electrons found in galaxy clusters against the faint afterglow from the Big Bang in the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Before this new result, astronomers assumed that at early cosmic epochs, galaxy clusters were still too immature to have fully developed and heated their intracluster gas.

No hot cluster atmospheres had been directly detected in the first 3 billion years of cosmic history.

“SPT2349-56 changes everything we thought we understood,” said Professor Scott Chapman, a researcher at Dalhousie University and the University of British Columbia.

“Our measurements show a superheated cluster atmosphere only 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, at a time when we thought the intracluster gas should still be relatively cool and slowly settling in.”

“It suggests that the birth of massive clusters could be much more violent and efficient at heating the gas than our models assumed.”

According to the study, powerful outbursts from SPT2349-56’s supermassive black holes, seen as bright radio galaxies, could be a natural way to inject the enormous amount of energy needed to overheat the intracluster gas so early.

The discovery suggests that in the Universe’s first billion years, energetic processes, like bursts from supermassive black holes and intense starbursts, could dramatically heat the surrounding gas in growing clusters.

This overheating stage could be crucial for transforming these young cool galaxy clusters into the sprawling hot clusters seen today.

It also suggests current models need to update ideas on how galaxies and their environments grow up.

This is the earliest direct detection of hot cluster gas ever reported, pushing the limits of how far back astronomers can study these environments.

The discovery that massive reservoirs of hot plasma exist so early forces scientists to rethink the sequence and speed of galaxy cluster evolution.

It also opens new questions about how supermassive black holes and galaxy formation shape the cosmos.

“SPT2349-56 is a very strange and exciting laboratory,” Zhou said.

“We see intense star formation, energetic supermassive black holes and this overheated atmosphere all packed into a young, compact cluster.”

“There is still a huge observational gap between this violent early stage and the calmer clusters we see later on.”

“Mapping how their atmospheres evolve over cosmic time will be a very exciting direction for future work.”

The results were published on January 5, 2026 in the journal Nature.

_____

D. Zhou et al. Sunyaev-Zeldovich detection of hot intracluster gas at redshift 4.3. Nature, published online January 5, 2026; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09901-3