A new study in rats led by Dr. Beth Allison of the University of Cambridge, UK, suggests that the aging clock begins ticking even before we are born and enter this world.

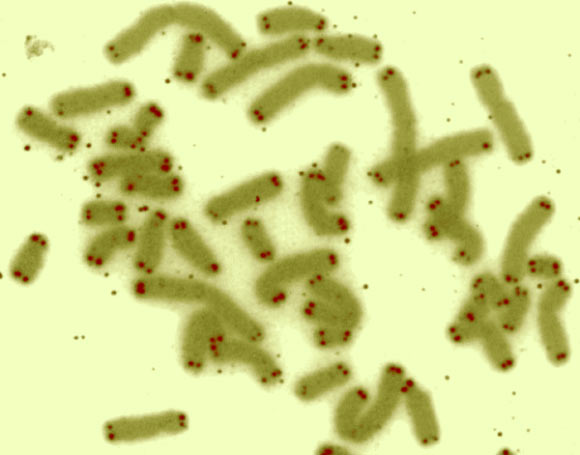

This false-color image shows human chromosomes (green) capped by telomeres (red). Image credit: U.S. Department of Energy Human Genome Program.

Dr. Allison and co-authors also found that providing mothers with antioxidants during pregnancy meant that their offspring aged more slowly in adulthood.

Our DNA is ‘written’ onto chromosomes, of which humans carry 23 pairs. The ends of each chromosome are known as telomeres and act in a similar way to the plastic that binds the ends of shoelaces, preventing the chromosomes from fraying.

As we age, these telomeres become shorter and shorter, and hence their length can be used as a proxy to measure aging.

Prof. Giussani and her colleagues from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands measured the length of telomeres in blood vessels of adult lab rats born from mothers who were or were not fed antioxidants during normal or complicated pregnancy.

“The most common complication in pregnancy is a reduction in the amount of oxygen that the baby receives – this can be due to a number of causes, including expectant mothers who smoke or who experience pre-eclampsia,” the scientists explained.

To simulate this complication, they placed a group of pregnant rats in a room containing 7% less oxygen than normal.

They found that adult rats born from mothers who had less oxygen during pregnancy had shorter telomeres than rats born from uncomplicated pregnancies, and experienced problems with the inner lining of their blood vessels – signs that they had aged more quickly and were predisposed to developing heart disease earlier than normal.

However, when pregnant mothers in this group were given antioxidant supplements, this lowered the risk among their offspring of developing heart disease.

Even the offspring born from uncomplicated pregnancies – when the fetus had received appropriate levels of oxygen – benefited from a maternal diet of antioxidants, with longer telomeres than those rats whose mothers did not receive the antioxidant supplements during pregnancy.

“We already know that our genes interact with environmental risk factors, such as smoking, obesity and lack of exercise to increase our risk of heart disease, but here we’ve shown that the environment we’re exposed to in the womb may be just as, if not more, important in programming a risk of adult-onset cardiovascular disease,” said study senior author Prof. Dino Giussani, from the University of Cambridge.

“Antioxidants are known to reduce aging, but here, we show for the first time that giving them to pregnant mothers can slow down the aging clock of their offspring,” Dr. Allison added.

“This appears to be particularly important when there are complications with the pregnancy and the fetus is deprived of oxygen.”

“Although this discovery was found using rats, it suggests a way that we may treat similar problems in humans.”

The results were published online March 1 in the FASEB Journal.

_____

Beth J. Allison et al. Divergence of mechanistic pathways mediating cardiovascular aging and developmental programming of cardiovascular disease. FASEB Journal, published online March 01, 2016; doi: 10.1096/fj.201500057