According to a study in rodents led by Prof. Charles Bourque of McGill University, the brain’s biological clock stimulates thirst in the hours before sleep.

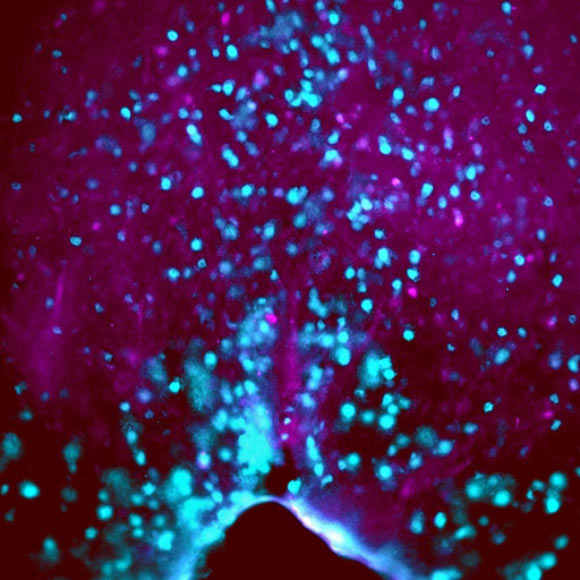

This image shows thirst neurons (blue) in mouse SCN. Image credit: C. Gizowski et al / McGill University.

Biologists knew that rodents show a surge in water intake during the last two hours before sleep.

The new study revealed that this behavior is not motivated by any physiological reason, such as dehydration. So if they don’t need to drink water, why do they?

Prof. Bourque and co-authors found that restricting the access of mice to water during the surge period resulted in significant dehydration towards the end of the sleep cycle.

So the increase in water intake before sleep is a preemptive strike that guards against dehydration and serves to keep the animal healthy and properly hydrated.

Then the team looked for the mechanism that sets this thirst response in motion.

It’s well established that the brain harbors a hydration sensor with thirst neurons in that sensor organ.

So they wondered if the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) — the brain region that regulates circadian cycles (biological clock) — could be communicating with the thirst neurons.

The researchers suspected that vasopressin, a neuropeptide produced by the SCN, might play a critical role.

To confirm that, they used so-called ‘sniffer cells’ designed to fluoresce in the presence of vasopressin.

When they applied these cells to rodent brain tissue and then electrically stimulated the SCN.

“We saw a big increase in the output of the sniffer cells, indicating that vasopressin is being released in that area as a result of stimulating the clock,” Prof. Bourque said.

To explore if vasopressin was stimulating thirst neurons, Prof. Bourque and his colleagues at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre employed optogenetics.

Using genetically engineered mice whose vasopressin neurons contain a light activated molecule, they were able to show that vasopressin does, indeed, turn on thirst neurons.

“Our findings reveal the existence of anticipatory thirst, and demonstrate this behavior to be driven by excitatory peptidergic neurotransmission mediated by vasopressin release from central clock neurons,” the scientists said.

“Although this study was performed in rodents, it points toward an explanation as to why we often experience thirst and ingest liquids such as water or milk before bedtime,” Prof. Bourque said.

“More importantly, this advance in our understanding of how the clock executes a circadian rhythm has applications in situations such as jet lag and shift work.”

“All our organs follow a circadian rhythm, which helps optimize how they function. Shift work forces people out of their natural rhythms, which can have repercussions on health. Knowing how the clock works gives us more potential to actually do something about it.”

This research was published in the September 29, 2016 issue of the journal Nature.

_____

C. Gizowski et al. 2016. Clock-driven vasopressin neurotransmission mediates anticipatory thirst prior to sleep. Nature 537: 685-688; doi: 10.1038/nature19756

This article is based on a press-release issued by McGill University.