Great tits (Parus major) pick their spring breeding sites to be near their winter flockmates, according to a new study by scientists at the University of Oxford, UK.

Two female great tits (Parus major). Image credit: Shirley Clarke / Fordingbridge Camera Club / CC BY-SA 3.0.

The study, published in the journal Ecology Letters, shows that as mated pairs of great tits settle down to breed in the spring, they establish their homes in locations close to their winter flockmates.

The birds also arrange their territory boundaries so that their most-preferred winter ‘friends’ are their neighbors.

“The great tits we study are a good general model for many other bird species,” said study lead author Dr. Josh Firth, a researcher at the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford.

“They form large flocks in the winter, when they’re searching for food, and then each pair chooses a single set breeding site where they will be located throughout the spring as they build a nest and raise their chicks.”

“We show that they appear to choose their spring breeding sites to stay close to their winter flockmates,” he added.

“Not only do they nest closest to the birds they held the strongest winter social bonds with, they also appear to arrange their territories so that they share home boundaries with those birds.”

“As well as telling us about the birds’ social behavior, this also has interesting implications for other aspects of biology,” Dr. Firth said.

“For instance, where an animal’s ‘home’ is determines the environmental factors they experience, such as weather conditions.”

“Therefore, as they appear to base their location choices around their social bonds, this indicates that their previous social associations can underpin the environment and conditions they will be subjected to in future.”

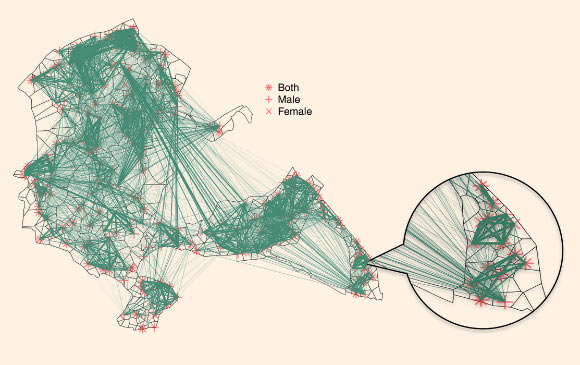

Illustrative breeding positions and winter social network of great tits from 2012 in Wytham Woods. Black dividing lines show the inferred territory boundaries around each individuals breeding location. Points show breeding sites of birds recorded in winter social network (star – both parents, cross – male, ‘X’ – female). Adjoining lines represent social associations recorded in the previous winter, and line thickness illustrates strength of association (mean strength is displayed for boxes where both parents were included). Image credit: Josh A. Firth / Ben C. Sheldon, doi: 10.1111/ele.12669.

The work was carried out in Wytham Woods, the University of Oxford’s research woodland near the city, on a great tit population that has been monitored since the 1960s.

Using data gathered from equipping thousands of birds with RFID (radio-frequency identification) tags to record their winter social interactions and spring nesting box choices over a three-year period (in 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively), Dr. Firth and his colleague, Dr. Ben Sheldon, were able to determine which birds were flockmates during the winter and, subsequently, where they settled in relation to each other in the spring.

“There may be benefits of choosing breeding locations based on previous social associations,” Dr. Firth said.

“For instance, we know that familiar birds are more likely to cooperate in fending off predators, and it may also reduce the amount of energy expended on competitive interactions, if individuals display less aggressive behavior towards familiar neighbors.”

_____

Josh A. Firth & Ben C. Sheldon. Social carry-over effects underpin trans-seasonally linked structure in a wild bird population. Ecology Letters, published online September 13, 2016; doi: 10.1111/ele.12669