A large team of genetic scientists led by Dr Qiaomei Fu of Harvard Medical School has recovered and sequenced the DNA from a thighbone of a male hunter-gatherer who lived in what is now Siberia 45,000 years ago.

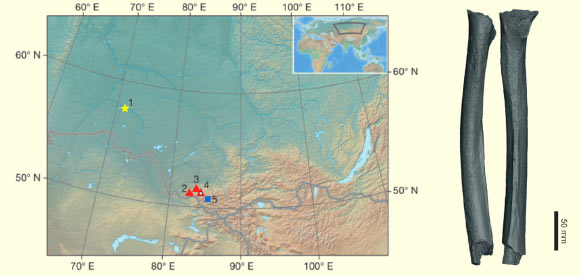

Left: map of Siberia with major archaeological sites: 1- Ust’-Ishim; 2 – Chagyrskaya Cave (Neanderthal fossils); 3 – Okladnikov Cave (Neanderthal fossils); 4: Denisova Cave (Denisovan fossils); 5: Kara-Bom (Upper Paleolithic site). Right: the Ust’-Ishim femur: lateral and posterior views. Image credit: Qiaomei Fu et al.

The thighbone was found on the bank of the Irtysh River in the Ust’-Ishim region, Siberia, in 2008.

Carbon dating and molecular analysis determined that the bone was from an individual who lived approximately 45,000 years ago on a diet that included plants or plant eaters and fish or other aquatic life.

The sample was remarkable because of the extraordinary preservation of its DNA, which allowed Dr Fu and her colleagues to extract a high-quality genome sequence, which is significantly higher in quality than most genome sequences of present-day people generated for analysis of disease risk.

The sequence revealed that the bone came from an anatomically modern human, a man whose remains are the oldest ever found and carbon-dated outside of Africa and the Middle East.

Comparison to diverse humans around the world today showed that the Ust’-Ishim man was a member of one of the most ancient non-African populations.

“The ancient Siberian was related equally to West European hunter-gatherers, North Asian hunter-gatherers, East Asians, and the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands off South Asia,” said Dr Fu, who is the first author of a paper published in the journal Nature.

“The fact that this population separated so early indicates that theories of an early split of people who followed a coastal route to Australia, New Guinea, and coastal Asia are not strongly supported by this data.”

The scientists also obtained a high-resolution estimate of the mutation rate in humans.

Previous studies had given scientists evidence of two possible rates, one twice as fast as the other. Because of this large range, dates obtained from genetic research have tended to be quite uncertain.

By measuring the number of mutations missing in the Ust’-Ishim man and comparing with people now, the scientists obtained an accurate estimate of the rate that mutations accumulated over time. They revealed a slower mutation rate, corresponding to between one to two mutations per genome per year.

“This is a huge biological result. It’s very important,” said co-author Prof David Reich of Harvard Medical School.

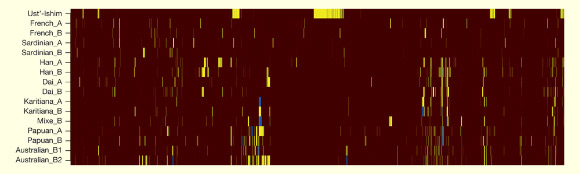

Regions of Neanderthal ancestry on chromosome 12 in the Ust’-Ishim individual and 15 present-day non-Africans: homozygous ancestral alleles are brown, heterozygous derived alleles are yellow, and homozygous derived alleles are blue. Image credit: Qiaomei Fu et al.

“The findings have sweeping implications and provide a basis for reinterpreting key dates in human prehistory.”

“Instead of humans and Neanderthals becoming distinct offshoots sometime between 270,000 and 380,000 years ago, for example, the slower rate would put that shift much further back in time, between 550,000 and 770,000 years ago.”

“Similarly, the slower rate pushes back estimates for the date of the separation of African and non-African populations.”

The slow mutation rates indicate that the present-day subdivisions among human populations date back to almost 200,000 years ago, well before the period around 50,000 years ago when the archaeological record documents art and new styles of tool-making.

“The implication is that the spread of modern human behavior must have been cultural, at least in part. Based on the genetic dates, it cannot be the case of a single population that developed modern human behavior spread all around the world replacing the other humans who already lived there.”

The researchers also found that about 2.3 percent of the Ust’-Ishim man’s genome came from Neanderthals.

The genomic segments of Neanderthal ancestry are substantially longer than those observed in present-day individuals, indicating that Neanderthal gene flow into the ancestors of this individual occurred 7,000-13,000 years before he lived (i.e. 58,000-52,000 years ago – a much tighter window than the previous range of between 37,000 and 86,000 years ago).

“The longer stretches of Neanderthal material may be the signature of mixing between Neanderthals and the ancestors of the Siberian individual within a few dozen generations of when he lived, though additional research is needed to ascertain that,” Dr Fu concluded.

_____

Qiaomei Fu et al. 2014. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449; doi: 10.1038/nature13810