A long-standing mystery in vertebrate evolution — why most major fish lineages appear suddenly in the fossil record tens of millions of years after their presumed origins — is tied to the Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME), according to a new analysis by paleontologists at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. The authors found that this mass extinction event, about 445 to 443 million years ago, triggered parallel, endemic radiations of jawed and related jawless vertebrates (gnathostomes) in isolated refugia, reshaping the early history of fishes and their relatives.

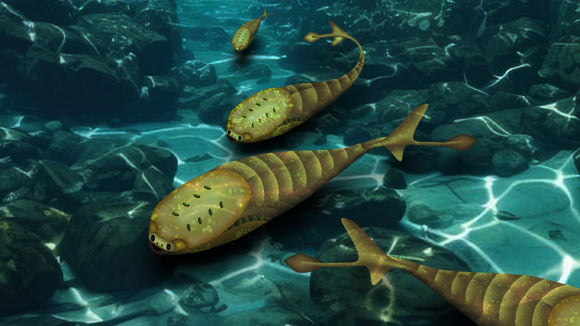

Life reconstruction of Sacabambaspis janvieri, a species of armored jawless fish that lived during the Ordovician period. Image credit: Kaori Serakaki, OIST.

Most vertebrate lineages are first recorded from the mid-Paleozoic, well after their Cambrian origin and Ordovician invertebrate biodiversification events. This delay has often been attributed to poor sampling and long ghost lineages.

Instead, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology paleontologists Wahei Hagiwara and Lauren Sallan suggest that LOME fundamentally reorganized vertebrate ecosystems.

Using newly-compiled global databases of Paleozoic vertebrate occurrences, biogeography, and ecosystems, they found that this mass extinction event coincided with the disappearance of ubiquitous stem-cyclostome conodonts (extinct marine jawless vertebrates), along with losses among early gnathostomes and pelagic invertebrates.

In the aftermath, post-extinction ecosystems hosted the first definitive appearances of most major vertebrate lineages of the Paleozoic ‘Age of Fishes.’

“While we don’t know the ultimate causes of LOME, we do know that there was a clear before and after the event. The fossil record shows it,” Professor Sallan said.

“We pulled together 200 years of Late Ordovician and Early Silurian paleontology, creating a new database of the fossil record that helped us reconstruct the ecosystems of the refugia,” Dr. Hagiwara said.

“From this, we could quantify the genus-level diversity of the period, showing how LOME led directly to a gradual, but dramatic increase in gnathostome biodiversity.”

LOME itself unfolded in two pulses during a period marked by prolonged global fluctuations in temperature, alterations in ocean chemistry including essential trace elements, sudden polar glaciation, and sea level changes.

These changes devastated marine ecosystems and produced a post-extinction ‘gap’ with low biodiversity. That gap persisted into the earliest Silurian.

The researchers confirm a previously proposed interval of missing vertebrate diversity known as Talimaa’s Gap.

During this time, global richness remained very low, and surviving faunas were composed almost entirely of isolated microfossils.

Recovery was slow: the Silurian period comprised a 23-million-year recovery interval, during which vertebrate lineages diversified gradually and intermittently.

Most Silurian gnathostome lineages diversified gradually and intermittently during an initial period of otherwise very low global richness.

Rather than spreading rapidly across ancient oceans, early jawed vertebrates appear to have evolved in isolation.

The scientists found a high level of endemism in gnathostomes from the very beginning of the Silurian, with diversification occurring in specific, long-lasting extinction refugia.

One such refugium was South China, where the earliest definitive evidence for jaws appears in the fossil record.

These early jawed vertebrates remained geographically restricted for millions of years.

Turnover and recovery following LOME matched those following climatically similar events like the end-Devonian mass extinction, including prolonged intervals of low diversity and delayed dominance of jawed fishes.

“In what is now South China, we see the first full-body fossils of jawed fishes that are directly related to modern sharks,” Dr. Hagiwara said.

“They were concentrated in these stable refugia for millions of years until they had evolved the ability to cross the open ocean to other ecosystems.”

“By integrating location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, we can finally see how early vertebrate ecosystems rebuilt themselves after major environmental disruptions,” Professor Sallan said.

“This work helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately prevailed, and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors rather than to earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites.”

The study was published January 9 in the journal Science Advances.

_____

Wahei Hagiwara & Lauren Sallan. 2026. Mass extinction triggered the early radiations of jawed vertebrates and their jawless relatives (gnathostomes). Science Advances 12 (2); doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aeb2297