Stevens Institute of Technology physicist Igor Pikovski and colleagues are developing the first experiment designed to capture individual gravitons — particles once thought fundamentally undetectable — heralding a new era in quantum gravity research.

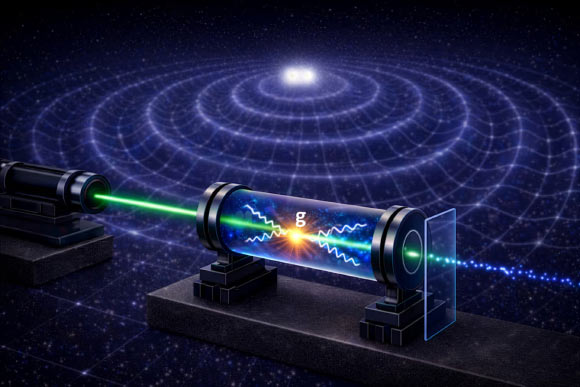

Signatures of single gravitons from gravitational waves can be detected in near-future experiments. Image credit: I. Pikovski.

Modern physics has a problem: its two main pillars are quantum theory and Einstein’s theory of general relativity, yet these two frameworks are seemingly incompatible.

Quantum theory describes nature in terms of discrete quantum particles and interactions, while general relativity treats gravity as a smooth curvature of space and time.

A true unification requires gravity itself to be quantum, mediated by particles known as gravitons.

However, detecting even a single graviton was long thought fundamentally impossible.

As a result, the problem of quantum gravity remained largely theoretical, with no experimentally grounded theory of everything in sight.

In 2024, Dr. Pikovski and colleagues from Stevens Institute of Technology, Stockholm University, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and Nordita showed that graviton detection is, in fact, possible.

“For a long time, graviton detection was considered so hopeless that it was not treated as an experimental problem at all,” Dr. Pikovski said.

“What we found is that this conclusion no longer holds in the era of modern quantum technology.”

The key is a new perspective that synthesizes two major experimental advances.

The first is the detection of gravitational waves: ripples in space-time produced by collisions of black holes or neutron stars.

The second advance comes from quantum engineering. Over the past decade, physicists have learned how to cool, control, and measure increasingly massive systems in genuine quantum states, bringing quantum phenomena far beyond the atomic scale.

In a landmark experiment in 2022, a team led by Yale University’s Professor Jack Harris demonstrated control and measurement of individual vibrational quanta of superfluid helium weighing over a nanogram.

Dr. Pikovski and co-authors realized that if these two capabilities are combined, it becomes possible to absorb and detect a single graviton; a passing gravitational wave can, in principle, transfer exactly one quantum of energy (i.e. a single graviton) into a sufficiently massive quantum system.

The resulting energy shift is small but can be resolved. The true difficulty is that gravitons almost never interact with matter.

But for quantum systems at the kilogram scale — rather than the microscopic scale — exposed to intense gravitational waves from merging black holes or neutron stars, absorbing a single graviton becomes possible.

Building on this recent discovery, Dr. Pikovski and Professor Harris have now teamed up to construct the world’s first experiment explicitly designed to detect individual gravitons.

With support from the W.M. Keck Foundation, they are developing a superfluid-helium resonator on the centimeter scale, approaching the regime required to absorb single gravitons from astrophysical gravitational waves.

“We already have the essential tools. We can detect single quanta in macroscopic quantum systems. Now it’s a matter of scaling,” Professor Harris said.

The experiment aims to immerse a gram-scale cylindrical resonator in a superfluid-helium container, cool the system to its quantum ground state, and use laser-based measurements to detect individual phonons — the vibrational quanta into which gravitons are converted.

The detector builds on systems already operating in a lab, but pushes them into a new regime, scaling the mass to the gram level while preserving exquisite quantum sensitivity.

Demonstrating the successful operation of this platform will establish a blueprint for a next iteration that can be scaled to the sensitivity required for direct graviton detection, opening a new experimental frontier in quantum gravity.

“Quantum physics began with experiments on light and matter,” Dr. Pikovski said.

“Our goal now is to bring gravity into this experimental domain, and to study gravitons the way physicists first studied photons over a century ago.”