Inspired by a technique that allowed astronomers to image a black hole, scientists at the University of Connecticut developed a lens-free image sensor that achieves sub-micron 3D resolution, promising to transform fields from forensics to remote sensing.

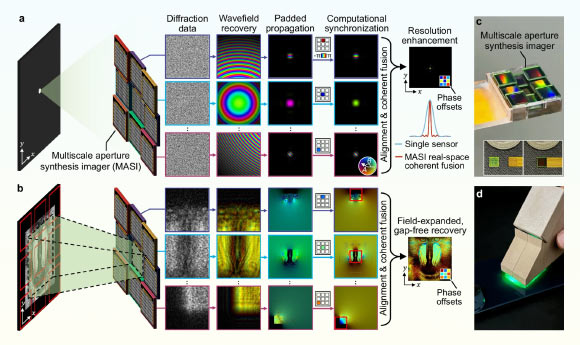

Operating principle and implementation of MASI. Image credit: Wang et al., doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8.

“At the heart of this breakthrough is a longstanding technical problem,” said University of Connecticut’s Professor Guoan Zheng, senior author of the study.

“Synthetic aperture imaging works by coherently combining measurements from multiple separated sensors to simulate a much larger imaging aperture.”

In radio astronomy, this is feasible because the wavelength of radio waves is much longer, making precise synchronization between sensors possible.

But at visible light wavelengths, where the scale of interest is orders of magnitude smaller, traditional synchronization requirements become nearly impossible to meet physically.

The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI) turns this challenge on its head.

Rather than forcing multiple optical sensors to operate in perfect physical synchrony, MASI lets each sensor measure light independently and then uses computational algorithms to synchronize the data afterward.

“It’s akin to having multiple photographers capture the same scene, not as ordinary photos but as raw measurements of light wave properties, and then letting software stitch these independent captures into one ultra-high-resolution image,” Professor Zheng said.

This computational phase synchronization scheme eliminates the need for rigid interferometric setups that have prevented optical synthetic aperture systems from practical deployment until now.

MASI deviates from conventional optical imaging in two transformative ways.

Rather than relying on lenses to focus light onto a sensor, MASI deploys an array of coded sensors positioned in different parts of a diffraction plane. Each captures raw diffraction patterns — essentially the way light waves spread after interacting with an object.

These diffraction measurements contain both amplitude and phase information, which are recovered using computational algorithms.

Once each sensor’s complex wavefield is recovered, the system digitally pads and numerically propagates the wavefields back to the object plane.

A computational phase synchronization method then iteratively adjusts the relative phase offsets of each sensor’s data to maximize the overall coherence and energy in the unified reconstruction.

This step is the key innovation: by optimizing the combined wavefields in software rather than aligning sensors physically, MASI overcomes the diffraction limit and other constraints imposed by traditional optics.

A virtual synthetic aperture for larger than any single sensor, enabling sub-micron resolution and wide field coverage without lenses.

Conventional lenses, whether in microscopes, cameras, or telescopes, force designers into trade-offs.

To resolve smaller features, lenses must be closer to the object, often within millimeters, limiting working distance and making certain imaging tasks impractical or invasive.

The MASI approach dispenses with lenses entirely, capturing diffraction patterns from centimeters away and reconstructing images with resolution down to sub-micron levels.

This is similar to being able to examine the fine ridges on a human hair from across a desktop instead of bringing it inches from your eye.

“The potential applications for MASI span multiple fields, from forensic science and medical diagnostics to industrial inspection and remote sensing,” Professor Zheng said.

“But what’s most exciting is the scalability — unlike traditional optics that become exponentially more complex as they grow, our system scales linearly, potentially enabling large arrays for applications we haven’t even imagined yet.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

_____

R. Wang et al. 2025. Multiscale aperture synthesis imager. Nat Commun 16, 10582; doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-65661-8