In 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 provided the only direct measurement of the radiation environment at Uranus. These findings established the well-accepted characterization of a system with a weaker ion radiation belt and surprisingly intense electron radiation belt. However, these observations may not have occurred during normal conditions. In a new study, Southwest Research Institute scientists compared the Voyager 2 observations to a similar event observed at Earth. Their approach, along with a recent reinterpretation of the Voyager 2 flyby, suggests that interaction between the solar wind and magnetosphere of Uranus may have resulted in enhanced electromagnetic waves capable of accelerating electrons to relativistic energies. This motivates new, more expansive questions to be explored at Uranus and highlights the need for a Uranus orbiter mission.

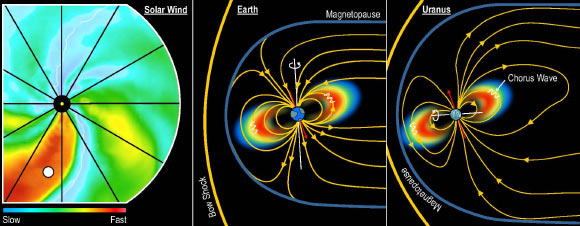

Allen et al. compared space weather impacts of a fast solar wind structure (first panel) driving an intense solar storm at Earth in 2019 (second panel) with conditions observed at Uranus by Voyager 2 in 1986 (third panel) to potentially solve a 39-year-old mystery about the extreme radiation belts found. Image credit: SwRI.

In 1986, when Voyager 2 made the first and only flyby of Uranus, it measured a surprisingly strong electron radiation belt at significantly higher levels than anticipated.

Based on extrapolations from other planetary systems, Uranus’ electron radiation belt was off the charts.

Since then, scientists have wondered how the Uranian system could support such an intense trapped electron radiation belt, at a planet unlike anything else in the Solar System.

Based on new analyses, Southwest Research Institute scientist Robert Allen and his colleagues theorize that Voyager 2 observations may have more in common with processes at Earth driven by large solar wind storms.

They think a solar wind structure — known as a co-rotating interaction region — was likely passing through the Uranian system.

This could explain the extreme energy levels Voyager 2 observed.

“Science has come a long way since the Voyager 2 flyby,” Dr. Allen said.

“We decided to take a comparative approach looking at the Voyager 2 data and compare it to Earth observations we’ve made in the decades since.”

The new study indicates that the Uranian system may have experienced a space weather event during the Voyager 2 visit that led to powerful high-frequency waves, the most intense observed over the entirety of the Voyager 2 mission.

“In 1986, scientists thought that these waves would scatter electrons to be lost to Uranus’ atmosphere,” Dr. Allen said.

“But since then, they have learned that those same waves under certain conditions can also accelerate electrons and feed additional energy into planetary systems.”

“In 2019, Earth experienced one of these events, which caused an immense amount of radiation belt electron acceleration,” said Southwest Research Institute scientist Sarah Vines.

“If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy.”

But these findings also raise a lot of additional questions about the fundamental physics and sequence of events that would enable these intense wave emissions.

“This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus,” Dr. Allen said.

“The findings have some important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune’s.”

The results appear in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

_____

R.C. Allen et al. 2025. Solving the Mystery of the Electron Radiation Belt at Uranus: Leveraging Knowledge of Earth’s Radiation Belts in a Re-Examination of Voyager 2 Observations. Geophysical Research Letters 52 (22): e2025GL119311; doi: 10.1029/2025GL119311