In a new paper published this month in the journal iScience, researchers from the University of Tübingen and elsewhere present a multidisciplinary analysis of stone and bone projectile points associated with Homo sapiens in the early Upper Paleolithic (40,000 to 35,000 years ago). By combining experimental ballistics, detailed measurements, and use-wear analyses, they conclude that some of these ancient artifacts were consistent with bow-propelled arrows, rather than only hand-thrown spears or spear-thrower darts.

Humans may have used bow-and-arrow in the early Upper Paleolithic as well as spear-throwers. Image credit: sjs.org / CC BY-SA 3.0.

For decades, archaeologists assumed a linear progression in weapon technologies: from handheld spears to spear-throwers and finally to bow and arrow.

But University of Tübingen researcher Keiko Kitagawa and colleagues argue that technology did not evolve in a simple sequence.

“Direct evidence for hunting weapons is rare in the archaeological record,” they said.

“Prehistoric hunting weapons range from handheld thrusting spears, which are effective for close-range hunting, to spear-on-spear-thrower as well as arrow-on-bow, which are used for medium or long-range hunting.”

“The earliest appearances of such tools are wooden spears and throwing sticks that date to 337,000-300,000 years ago in Europe.”

“Antler objects interpreted as spear-thrower hooks begin to be documented in Upper Solutrean contexts (c. 24,500-21,000 years ago), and they become more visible in the Magdalenian (from 21,000 yars ago) from Southwestern France with almost a hundred specimens.”

“Meanwhile, bow-and-arrow technology is only found in exceptionally well-preserved contexts at the Final Paleolithic sites of Mannheim-Vogelstang and Stellmoor, Germany, dated to 12,000 years ago, and at the Early Mesolithic site of Lilla Loshults Mosse, Sweden (c. 8,500 years ago), making it much younger than other projectile technologies.”

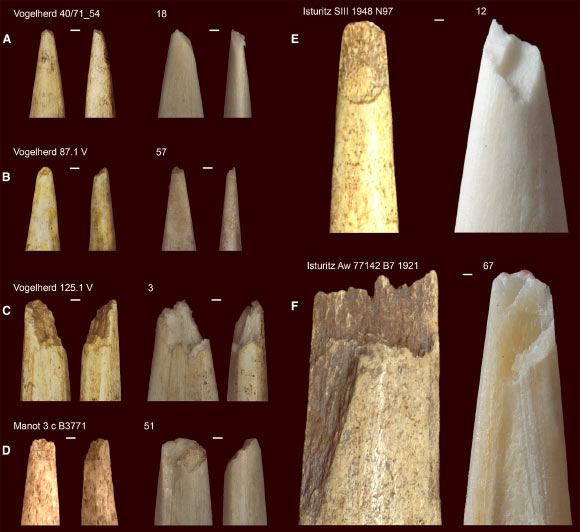

Archaeological examples from Aurignacian sites: Vogelherd in Germany, Isturitz in France, and Manot in Israel compared with experimental specimens. Image credit: Kitagawa et al., doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270.

In their paper, the authors suggest that early modern humans likely experimented with multiple systems simultaneously or in overlapping phases, reflecting varied adaptations to different ecosystems and prey types.

The evidence hinges on how these ancient projectile points break and wear when used.

When stone and bone points were fixed to shafts and launched in controlled experiments, the patterns of breakage and microdamage for some specimens matched what one would expect from arrows shot from a bow, not solely from spears or darts.

“We focus on the Upper Paleolithic osseous projectile implements, including the split- and massive-based points made of antler and bone, which were mostly found in Aurignacian contexts in Europe and the Levant between 40,000 and 33,000 years ago,” the scientists said.

“Our aim is to investigate whether it is possible to establish the type of weapons on which Aurignacian osseous projectile points were assembled from the use-wear patterns they bear and their morphometry.”

The findings dovetail with earlier archaeological research showing evidence of bow and arrow use in Africa as far back as roughly 54,000 years ago — older than once thought and predating parts of the European archaeological record.

Importantly, the team does not claim that Homo sapiens invented the bow simultaneously everywhere, nor that bows were the exclusive weapon.

Instead, it suggests a diverse technological repertoire at an early stage of human expansion into new territories.

“Our study in part demonstrates the complex nature of reconstructing projectile technology, which is often created with perishable materials,” the researchers concluded.

“While it is impossible to account for all variables that affect the physical properties of the armatures and the resulting damages, a series of experimental programs that is designed to address multi-faceted nature of projectiles in the future can hopefully shed more light onto one of the important pillars of hunter-gatherer’s economy.”

_____

Keiko Kitagawa et al. Homo sapiens could have hunted with bow and arrow from the onset of the early Upper Palaeolithic in Eurasia. iScience, published online December 18, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.114270